Ginger is a well known spice and flavoring agent which has also been used in traditional medicine in many countries. This large seasonal plant is cultivated in Southeast Asia and China, India, and some parts of Africa. Ginger and turmeric plants have several similar characteristics – both possess pale green flowers and are surrounded by long lanceolate leaves.

Ginger, a source of valuable phytonutrients, is characterized as having an aromatic odor and a pungent taste1. The part of the ginger plant that is used is the root, which is botanically the rhizome. The flat surfaces of the rhizome are removed, leaving the remains of the underground stem2. Ginger contains essential oils including gingerol and zingiberene. It also contains pungent principles such as zingerone, gingerol and shogaol3.

For centuries, in Ayurvedic and Tibetan systems of medicine, ginger has been used in the management of headache, nervous diseases, nausea, and vomiting. Ginger has been noted to treat migraine headaches without side-effects4. In addition, it is also recommended in the management of rheumatic disorders and muscular pain5.

Chemistry

The ginger rhizome has the following chemical composition:

- 60% starch,

- 10% proteins,

- 10% fats,

- 5% fibers,

- 6% inorganic material,

- 10% residual moisture,

- 1-4% essential oil5.

The percentage of essential oil varies with geographic origin. However, its chief elements, sesquiterpene hydrocarbons, remain constant. These include (-)-zingiberene, (+)-ar-curcumene, (-)-ß-sesquiphellandrene, E, E- a -farnesene, and b -bisabolene. These essential oils occur alongside monoterpene alcohols and aldehydes present as glycosides. A mixture of many terpenes and some non-terpenoid compounds make up the essential oil.1 It has been speculated that since there are a variety of chemical classes that these compounds can belong to, it is likely that ginger can eliminate symptoms associated with a variety of illnesses, such as arthritis, by interfering with the production and release of metabolic products from lipid membranes, peptides, proteins and amino acids.

Experimental data reveal that ginger may be a dual inhibitor of eicosanoid synthesis, inhibiting the synthesis of both prostaglandins and leukotrienes, which are inflammatory mediators produced from arachidonic acid5.

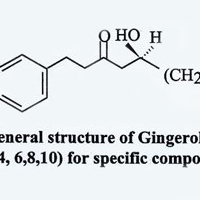

The rhizome contains a variety of chemicals called gingerols which provide its distinctive taste and characteristic pharmacological effects. The chemical constituents responsible for the pungent taste of ginger are 1-(3’ –methoxy –4’-hydroxypheny1)-5-hydroxyalkan- 3-ones, also known as [3-6]-,[8]-,[10]-,and [12]-gingerols.1

Biological Effects and Clinical Uses

In recent years, researchers have scientifically validated many of the therapeutic uses of ginger.

-

- One study indicates that ginger is effective in reducing inflammation in arthritic conditions. In a study conducted with 56 patients experiencing either rheumatoid arthritis, osteoarthritis, or muscular discomfort, 75% experienced relief in pain and swelling after using powdered ginger. Furthermore, none of the patients complained of any side effects while using ginger to treat their symptoms. It is suggested that ginger works as an inhibitor of prostaglandin and leukotriene biosynthesis to produce its ameliorative effects.5

- Another case study presented ginger as a preventive agent for migraine headache. In this application, one subject was given non-steroidal antiinflammatory medication to permit her migraine headaches to subside. However, even though her headache was eliminated in time, other side effects including depression and redness of the eyes appeared. The subject was then given ginger. With 500-600 mg of powdered ginger mixed with water, the migraine headaches ceased within 30 minutes. In addition, after the cessation of the migraine attack, the subject did not experience any side effects. Migraine headaches are an accumulation of pain syndromes.

Many anitihistamines are used to treat migraines. Ginger has been shown to contain antihistamine and antioxidant factors as well as possess anti-inflammatory action4.

-

- The effect of ginger on stimulation of bile secretion was studied to identify the basis of its action as a metabolism enhancer. Results of this specific study reported that the acetone extracts of ginger, comprised of the essential oils and the pungent principles, produce an increase in bile secretion. The two pungent principles that were chiefly accountable for the cholagogic effect of ginger include [6]-gingerol and [10]-gingerol. Bile acids facilitate absorption of fat and electrolytes and peristalsis of the small intestine. Since ginger has been reported to increase bile secretion, it may be beneficial in the excretion of gallstones.3

-

- Furthermore, a study was done on 20 healthy male individuals that were given 50 g of butter and 5g of ginger a day for seven days. Addition of five grams of ginger with a fatty meal inhibited the platelet aggregation induced by adenosine diphosphate and epinephrine to a large extent. Ginger has been reported to inhibit prostaglandin synthesis in It has been reported that dietary fat content affects platelet aggregation by modifying prostaglandin metabolism. Inhibiting the transformation of arachidonic acid to thromboxane and decreasing the sensitivity of platelets to many aggregating agents may be possible with the administration of ginger in a fatty diet.6

- In view of the fact that ginger root has been used in several parts of the world in the management of motion sickness, researchers attempted to elucidate the mechanism of action. In one of the earlier studies, it was proposed that ginger constituents may increase gastric motility and prevent the accumulation of toxic substances, thereby blocking the gastrointestinal reactions which trigger the nausea feedback8. A more recent study addressed the role of ginger in preventing the nausea feedback at the nerve receptor level. In motion sickness, nausea and vomiting are mediated by specific receptors in the central and peripheral nervous system. These receptors are activated by the chemical messengers, acetylcholine and histamine. Ginger produces antimotion sickness action probably through anticholinergic and antihistaminic effects9.

The above studies indicate the inhibitory effects of ginger on synthesis of inflammatory mediators and the beneficial effects of powdered ginger as well as the isolated gingerols on digestion and metabolism. In view of these effects, ginger is a potential herbal alternative in the management of digestive disorders, migraine, painful arthritic conditions and motion sickness. The herb may be potentially useful in improving blood circulation as well, on account of its inhibitory effects on platelet aggregation. When used as a spice or therapeutically at the recommended levels, [for motion sickness: 300 mg of the extract (containing 5% gingerols) daily in divided doses; for digestive distress: (75 mg of the extract daily in divided doses)], ginger does not have any reported side effects7.

References

- Bruneton, Jean. (1995) Ginger. Pharmacognosy, Phytochemistry, Medicinal plants, Lavoisier publishing Co.Inc. 258-261.

- Bisset, N.G. (Ed.). Max Wichtl. Herbal Drugs and Phytopharmaceuticals: A Handbook for practice on a scientific basis. Stuttgart: Medpharm Scientific Publishers CRC, 1994,537-539.

2a. Mowrey, D.B., Clayson, D.E.(1982) Motion Sickness, ginger, and psychotropics. Lancet: 655-657.

2b. Shoji, N. et al. (1982) Cardiotonic principles of ginger. Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 71 (10): 1174-1175,.

2c. Tyler, V. The Honest Herbal: A Sensible Guide to the Use of Herbs and Related Remedies. Birmingham, New york: Pharmaceutical products, Press,1993. 147-148.

- Yamahara, J. et al. (1985) Cholagogic Effect of Ginger and Its Active Constituents. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 13: 217-225.

- Mustafa, T. and Srivastava K.T. (1990) Ginger (Zingiber Officinale) in Migraine Headache. Journal of Ethnopharmacology, 29: 267-273.

- Srivastava, K.C. and Mustafa, T. (1992) Ginger (Zingiber Officinale) in Rheumatism and Musculoskeletal Disorders. Medical Hypothesis, 39: 342-348.

- Verma, S.K. et al. (1993) Effect of Ginger on Platelet Aggregation in Indian Journal of Med Res, 98: 240-242.

- Zingiber officinale in Selected Medicinal Plants of India (A Monograph of Identity, Safety and Clinical Usage), CHEMEXIL, 1992,pp 362.

- Mowrey, D.B.(1982)Motion sickness, ginger and psychophysics. The Lancet, March 20, 656.

- Qian, DS and Liu ZS (1992) Pharmacologic Studies of Antimotion Sickness Actions of Ginger. Chung Ho Chung Hsi I Chieh Ho Tsa Chih, 12 (2): 95-8,70.